Reuters

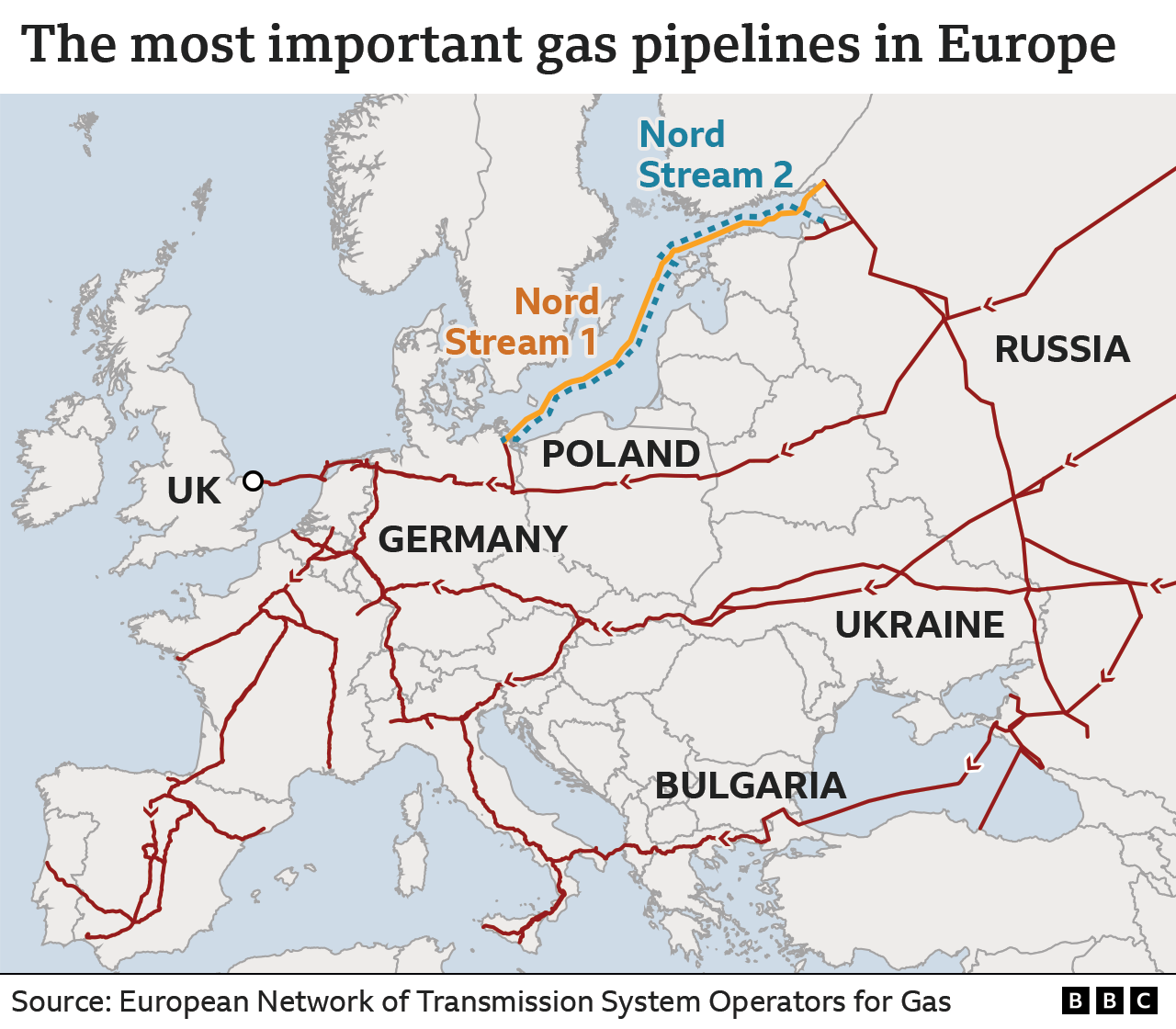

ReutersThis is no coincidence. Russia's state-controlled gas giant announced an indefinite extension to a three-day maintenance halt to flows of gas through the continent's key energy artery, hours after leading western finance ministers vowed to escalate sanctions on Russian oil.

Gazprom's official reason is that an oil leak has been found and the pipeline cannot work without German imports of technology, which are now subject to sanctions.

Few observers believe, however, that this is anything other than an attempt essentially to blackmail Europe over supplies.

The G7 world's main economies, including the UK, agreed to cap the price they pay for oil from Russia. This is a way to limit the revenues that fund the Kremlin's war in Ukraine - it earns more from oil exports than gas.

But this is a very serious development. Even during the height of the Cold War, Russia kept supplies of its gas flowing into Europe.

This cut-off though - and the pointed attempt by Gazprom to blame the German energy giant Siemens for the malfunction - is the culmination of decades of dysfunction in the energy relationship between Russia and Germany.

For most of that time, of course, Bonn and then Berlin were delighted to avail themselves of cheap Russian gas.

A younger Vladimir Putin did his PhD thesis on the importance of Russian energy exports.

When I visited Gazprom's headquarters a decade ago and its fields in Siberia, I was told menacingly "anyone who artificially tries to diminish the role of Russian gas is playing a very dangerous game". A visit to the Novi Urengoy field showed Gazprom consolidating its hold on the Russian state, with some assistance from Berlin.

Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder enshrined this dependence with the building of this same Nordstream pipeline, which then gave him a job on its board. Gazprom sponsored German football, Europe's premier football competition the Champions League, and bankrolled various Russian soft power projects.

Perhaps most incredibly, German industry swapped the gas storage facilities under its soil for privileged access to deep-lying gas reserves under the Siberian tundra.

The very facilities, including Germany's largest, designed for resilience in the face of Russian energy diplomacy were passed into Russian ownership. It beggars belief that this was completed in 2015, after Russia's annexation of Crimea.

One sliver of hope, though, now lies in those same storage facilities. The German government seized ownership of the storage facilities that had been left at very low levels last year.

There, and across the continent, energy companies backed by government loans have spent the summer buying up as much gas as possible at any price.

The major economies are now on course to fill massive stores of gas, designed to cope with a cut to supplies of several weeks. Germany's huge stores are now 84% full, having been less than half full in June.

As a result, gas prices traded in international markets have come down from extreme highs over the past week. But they are still very high by normal standards.

There remains a dash to secure alternative supplies that is pushing up the price for all countries, including Britain. And the true impact of all this will depend on just how long the pipeline outage lasts.

But surely now, for Germany and the rest of Europe, there will be no going back to reliance on Russia.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiKmh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmJiYy5jb20vbmV3cy9idXNpbmVzcy02Mjc3OTkwOdIBLmh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmJiYy5jb20vbmV3cy9idXNpbmVzcy02Mjc3OTkwOS5hbXA?oc=5

2022-09-03 12:25:36Z

1551659288