India has launched its third Moon mission, aiming to be the first to land near its little-explored south pole.

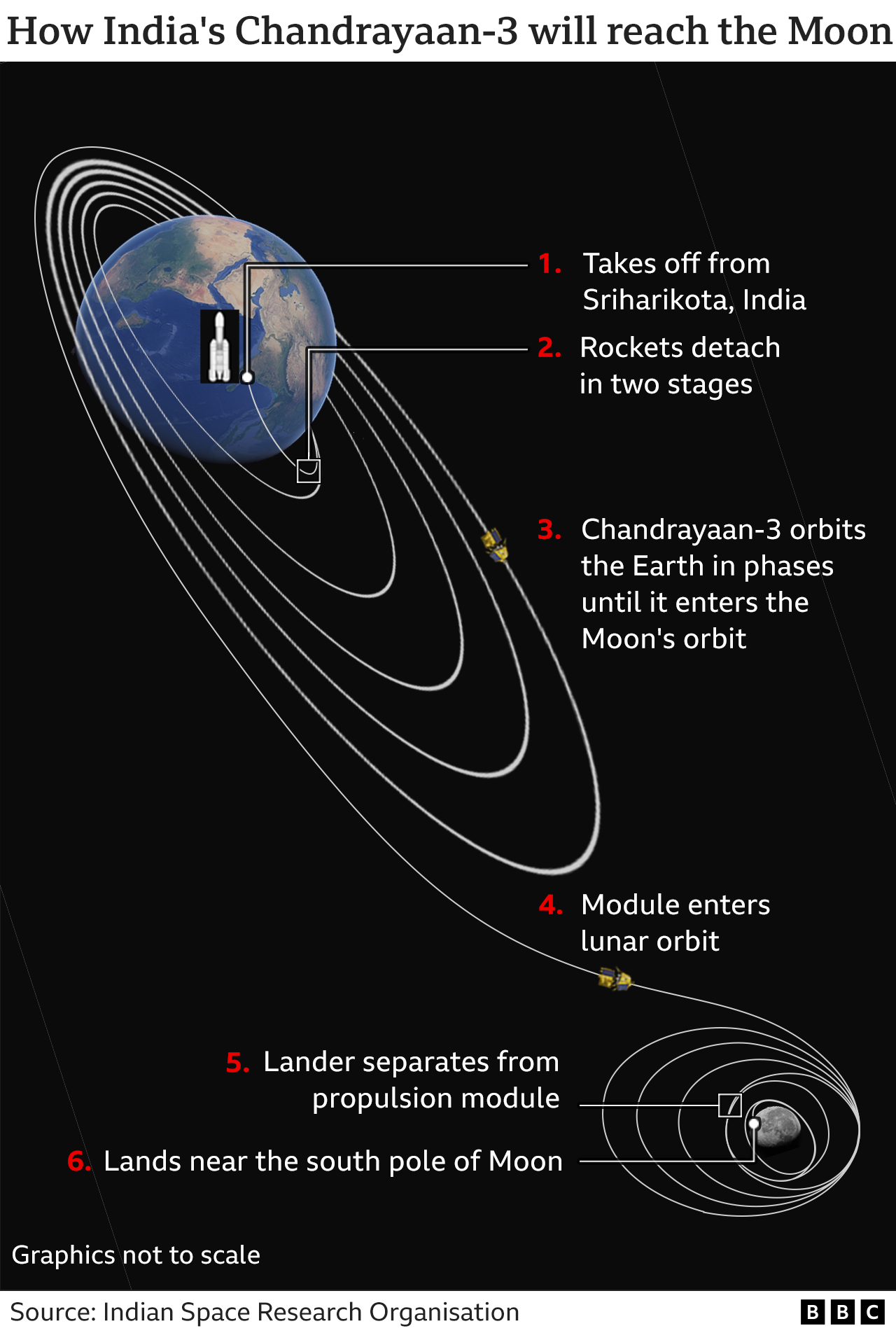

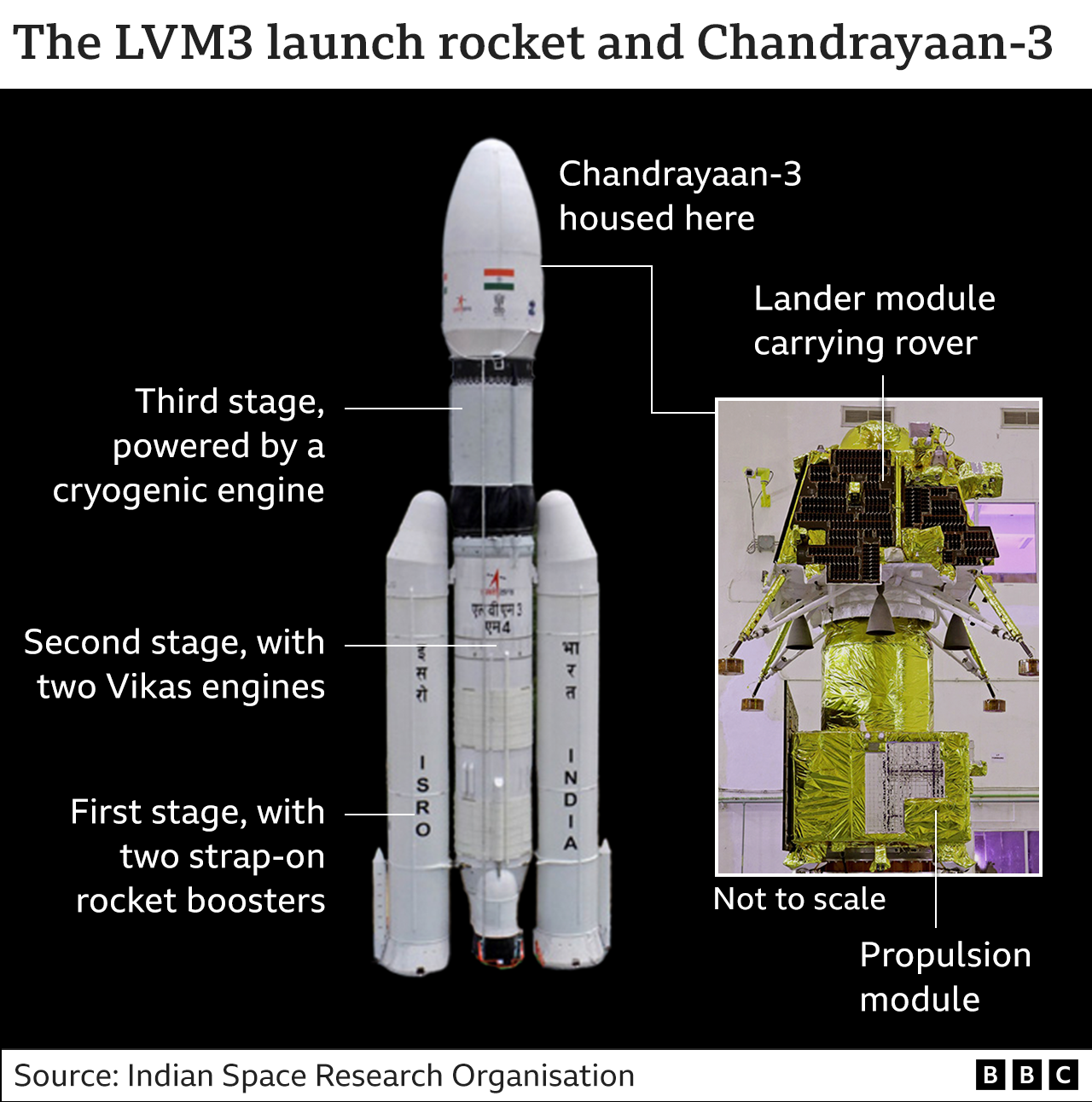

The Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft with an orbiter, lander and a rover lifted off at 14:35 on Friday (09:05 GMT) from Sriharikota space centre.

The lander is due to reach the Moon on 23-24 August, space officials said.

If successful, India will be only the fourth country to achieve a soft landing on the Moon, following the US, the former Soviet Union and China.

The third in India's programme of lunar exploration, Chandrayaan-3 is expected to build on the success of its earlier Moon missions.

It comes 13 years after the country's first Moon mission in 2008, which carried out "the first and most detailed search for water on the lunar surface and established the Moon has an atmosphere during daytime", said Mylswamy Annadurai, project director of Chandrayaan-1.

Chandrayaan-2 - which also comprised an orbiter, a lander and a rover - was launched in July 2019 but it was only partially successful. Its orbiter continues to circle and study the Moon even today, but the lander-rover failed to make a soft landing and crashed during touchdown. It was because of "a last-minute glitch in the braking system", explained Mr Annadurai.

Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) chief Sreedhara Panicker Somanath has said they have carefully studied the data from the last crash and carried out simulation exercises to fix the glitches.

Chandrayaan-3, which weighs 3,900kg and cost 6.1bn rupees ($75m; £58m), has the "same goals" as its predecessor - to ensure a soft-landing on the Moon's surface, he added.

The lander (called Vikram, after the founder of Isro) weighs about 1,500kg and carries within its belly the 26kg rover which is named Pragyaan, the Sanskrit word for wisdom.

After Friday's lift-off, the craft will take about 15 to 20 days to enter the Moon's orbit. Scientists will then start reducing the rocket's speed over the next few weeks to bring it to a point which will allow a soft landing for Vikram.

If all goes to plan, the six-wheeled rover will then eject and roam around the rocks and craters on Moon's surface, gathering crucial data and images to be sent back to Earth for analysis.

"The rover is carrying five instruments which will focus on finding out about the physical characteristics of the surface of the Moon, the atmosphere close to the surface and the tectonic activity to study what goes on below the surface. I'm hoping we'll find something new," Mr Somanath told Mirror Now.

The south pole of the Moon is still largely unexplored - the surface area that remains in shadow there is much larger than that of the Moon's north pole, which means there is a possibility of water in areas that are permanently shadowed. Chandrayaan-1 was the first to discover water on the Moon in 2008, near the south pole.

"We have more scientific interest in this spot because the equatorial region, which is safe for landing, has already been reached and a lot of data is available for that," Mr Somanath said.

"If we want to make a significant scientific discovery, we have to go to a new area such as the south pole, but it has higher risks of landing."

Mr Somanath adds data from Chandrayaan-2 crash has been "collected and analysed" and it has helped fix all the errors in the latest mission.

"The orbiter from Chandrayaan-2 has been providing lots of very high-resolution images of the spot where we want to land and that data has been well studied so we know how many boulders and craters are there and we have widened the domain of landing for a better possibility."

The landing, Mr Annadurai said, would have to be "absolutely precise" to coincide with the start of a lunar day (a day on the Moon equals 14 days on Earth) because the batteries of the lander and the rover would need sunlight to be able to charge and function.

The Moon mission, Mr Annadurai says, was thought up in the early 2000s as an exciting project to attract talent at a time of the IT boom in India, as most technology graduates wanted to join the software industry.

"The success of Chandrayaan-1 helped on that count. The space programme became a matter of pride for India and it's now considered very prestigious to work for Isro."

But the larger goal of India's space programme, Mr Annadurai says, "encompasses science and technology and the future of humanity".

India is not the only country with an eye on the Moon - there's a growing global interest in it. And scientists say there is still much to understand about the Moon that's often described as a gateway to deep space.

"If we want to develop the Moon as an outpost, a gateway to deep space, then we need to carry out many more explorations to see what sort of habitat would we be able to build there with the locally-available material and how will we carry supplies to our people there," Mr Annadurai says.

"So the ultimate goal for India's probes is that one day when the Moon - separated by 360,000km of space - will become an extended continent of Earth, we will not be a passive spectator, but have an active, protected life in that continent and we need to continue to work towards that."

And a successful Chandrayaan-3 will be a significant step in that direction.

Sign up for our morning newsletter and get BBC News in your inbox.

Related Topics

https://news.google.com/rss/articles/CBMiNGh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmJiYy5jby51ay9uZXdzL3dvcmxkLWFzaWEtaW5kaWEtNjYxODU1NjXSAThodHRwczovL3d3dy5iYmMuY28udWsvbmV3cy93b3JsZC1hc2lhLWluZGlhLTY2MTg1NTY1LmFtcA?oc=5

2023-07-14 09:13:07Z

2171579814