"It is with profound sadness that I announce the death of a great man of an African state," Kenyatta said in a statement.

He ordered a period of national mourning and all flags to fly at half-mast until a state funeral is held at a later date.

The former president died in hospital in the early hours of Tuesday morning surrounded by his family, Kenyatta said.

He had been hospitalized in October for breathing problems but was discharged after a few weeks.

An autocratic rule

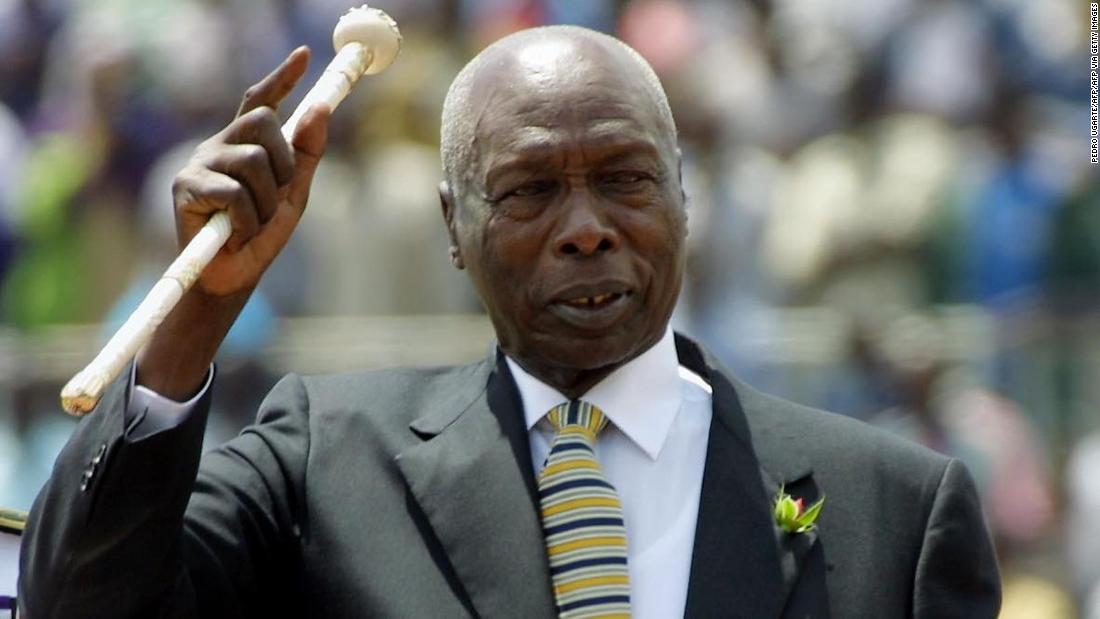

Daniel Arap Moi was Kenya's second President since independence and went on to rule the East African Republic from 1978 to 2002.

Born on September 2nd 1924 in Baringo County, Moi became the oldest living former Kenyan president, and his wily grasp of power earned him the nickname "Professor of Politics" amongst Kenyans.

His 24 years in power encompassed one party rule through the Kenyan African National Union, the party he controlled, and finally the reintroduction of democracy and multiparty politics, which culminated in his victory in the 1992 Presidential elections.

Educated at missionary and government schools, Moi became a teacher, as Kenya was moving towards independence from British rule.

He became the Minister of Home Affairs and President Jomo Kenyatta later named him Vice President in 1967.

Moi became Kenya's new leader after Kenyatta's death in 1978 heralding an era of autocratic and at times dictatorial rule.

Quashing rebellion

He toured the country and came into contact with ordinary people, boosting his popularity. Four years after coming to power, a coup was attempted by some members of the air force which Moi successfully crushed. His reaction was to send out military and police forces to quash the rebellion.

As a result, Moi's rule became more hardnosed -- he dismissed political opponents and reduced the influence of his predecessor Kenyatta's men in cabinet. He issued pardons for all except the main conspirators -- whom he sentenced to hang.

He went further to change the constitution and made his KANU party the only legally permitted political entity, triggering the wrath of many Kenyans who sought democracy.

The Moi regime then began to make more use of the secret police, who penetrated opposition groups agitating for democratic reforms.

Pressure from Western backers forced Moi back onto the democratic path in 1990 and he was compelled to allow opposition parties on to the ballot before the 1992 general elections, Kenya's first multi-party elections, which Moi won, despite allegations of electoral fraud by his party.

A violent time

Writers, artists trade unionists and even preachers agitating for a more diverse political atmosphere clashed with Moi's hard-line stance on dissent and single party rule.

One was the Reverend Timothy Njoya, 66, now a retired Presbyterian Church of East Africa Minister, who holds a Doctor of Philosophy degree from Princeton University.

As Moi's one-party state entrenched itself, Njoya was among those who chose to speak out against it, using his pulpit to urge civil disobedience to force the government to change the constitution, even demonstrating in the streets.

Speaking to CNN, Njoya recalled: "I was arrested so many times - one time in Nyeri the other time in Naivasha, again in Moro Rift Valley; then another time in Nairobi for saying that Kenyans should not pay taxes."

It was a violent time, full of overbearing state security operatives and deaths on the streets in various protests. And people like Njoya paid a heavy price. First, he was defrocked at Moi's insistence in 1997 and lost his collar. Then he almost lost his life too.

"I was almost killed at All Saints Cathedral. They left me for dead and I was being taken to the mortuary until a doctor insisted I should be taken to the Intensive Care Unit at Nairobi Hospital. I had a broken skull which was a centimetre from touching the brain. I had a fractured wrist. All four fingers on one hand were broken. I had to go to Canada for treatment. According to the doctor I had 52 injuries on my body including many broken ribs."

Two years later Njoya says Moi sent his henchmen after him again.

"That time they left me for dead again. They had used 'pangas', you know those long knives. I lost three of my fingers, but they were sewn back by the doctors. But emerging from hospital I went back on the streets because I couldn't disappoint the people."

Widespread influence

By now Moi's Kenya was firmly on the geopolitical map, particularly after jihadist terrorists blew up the US Embassy in Nairobi and the West sought to coopt him in the fight against terrorism when Bill Clinton was in the White House.

As a statesman Moi had widespread influence in cementing East African countries like Uganda, Tanzania into a coherent trading block. On the 14th of March 1996, full East African Cooperation efforts began and in July 1999 the new East African Community was born.

He also rallied to the cause of anti-apartheid in Southern Africa, sending Kenyan soldiers into pre-independence Zimbabwe as peacekeepers during the ceasefire there in 1979.

While he was the Chairman of the Organisation of African Unity, Moi was involved in securing peace in Chad. In Sudan, Moi chaired the talks that led to a referendum which ended a three-decade war in South Sudan and the creation of a new nation on the 9th of July 2011.

With 24 years at the helm of Kenya's government, Moi had a massive impact in shaping Kenya's politics and governmental structures. Subsequent presidents, Kibaki and Kenyatta, can be said to have been appointed by the elder statesman.

He appointed Kibaki as his Vice President and paved the way for him to later lead Kenya. He then plucked a largely unknown and untested Uhuru Kenyatta from relative obscurity and pushed him to the forefront of Kenyan politics.

A mixed and controversial legacy

As a former teacher, Moi's legacy also included a wide expansion of higher education. It was during the Moi era that the university sector grew starting with the opening of Kenya's second university in Eldoret, a town in the north.

A clutch of new universities were soon opening up, including private educational institutions run by Methodists. Today Kenya has more than 60 universities and public university colleges.

Daniel Arap Moi's life touched many Kenyans during a mixed and controversial 24 years - the longest rule of any leader in this powerhouse of East Africa.

Despite their differences Reverend Timothy Njoya says "Moi is the best President that ever lived," Njoya told CNN.

"Even if we had fought and died for multiparty democracy, he was the one who declared it. We were the ones who wanted a new constitution and he was the one who declared it. Admission to a mistake is the greatest thing in humanity. Future leaders can learn to admit when they are wrong."

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiQWh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmNubi5jb20vMjAyMC8wMi8wNC93b3JsZC9hZnJpY2EvZGFuaWVsLWFyYXAtbW9pLW9iaXQv0gFPaHR0cHM6Ly9hbXAuY25uLmNvbS9jbm4vMjAyMC8wMi8wNC93b3JsZC9hZnJpY2EvZGFuaWVsLWFyYXAtbW9pLW9iaXQvaW5kZXguaHRtbA?oc=5

2020-02-04 09:10:00Z

52780590350306

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar