The new German government being sworn in on Wednesday amounts to an unprecedented political experiment. The three coalition parties — Social Democrats, Greens and liberal Free Democrats — have never governed together before. And a host of urgent issues, not least a sharp escalation of the coronavirus pandemic, could subject their alliance to immediate strain. How they cope with the challenges outlined below will shape history’s verdict on their coalition.

1 — Overcoming coronavirus

Olaf Scholz’s cabinet takes power with Germany in the grip of a fourth Covid-19 wave that has dwarfed previous surges. Infection rates are soaring and hospitals reaching the limits of their capacity. Faced with an inoculation rate that is far lower than in countries such as Spain, Denmark and Belgium, the new chancellor has advocated mandatory vaccinations for all. But even those willing to get a jab face hurdles: lengthy queues form every day outside vaccination centres and doctors’ practices have complained of a shortage of shots. Meanwhile social tensions are growing: last week anti-lockdown protesters held a torch parade outside the home of a regional health minister, a protest widely condemned by politicians in Berlin.

2 — A sputtering economy

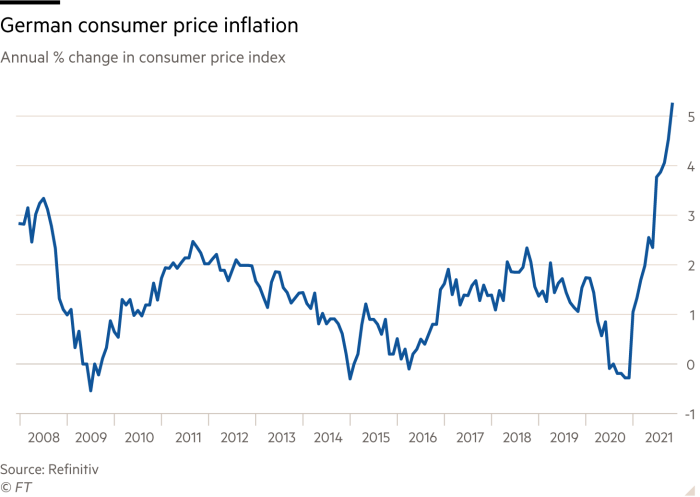

Scholz faces a much grimmer economic outlook than when his SPD narrowly won the election in September. Data released on Monday showed a far larger slump in factory orders than analysts had predicted. Industry has been plagued by shortages of raw materials and products such as microchips, which have led to delivery bottlenecks and production problems in the automobile industry. Meanwhile, inflation hit 6 per cent last month, its highest level since the early 1990s. Experts now believe Germany could take longer to return to pre-pandemic levels of economic growth than the eurozone overall. Business groups also fear that tough new restrictions on the unvaccinated, introduced last month, could suppress consumer activity in the run-up to Christmas.

3 — Meeting climate goals while keeping the lights on

Nowhere are the new government’s ambitions so clearly in evidence as in its plan for fighting climate change. It wants to massively ramp up renewables capacity, exit coal power by 2030 — eight years earlier than originally planned — phase out petrol and diesel cars and have 15m electric vehicles on Germany’s roads by the end of the decade. But some experts have questioned how the country will be able to keep the lights on once all its coal and nuclear power stations are closed. It will need to build thousands of new wind turbines and solar panels, extensive new electricity grids and a swath of gas-fired power stations. Indeed, talk is of a looming “electricity gap”, with industrial and residential consumers facing a potential energy shortfall and rising prices. The new government will have to figure out how to bridge this gap and achieve its green targets without endangering Germany’s export-driven economy.

4 — Foreign policy challenges

Days before Germany’s new government took office, US president Joe Biden warned US allies that Russia may be poised to invade Ukraine. Germany, along with others in Nato and the EU, now accepts this assessment and will probably sign up for hefty new sanctions should the Russians do so. But that could prove to be one of the first big tests of the coalition’s cohesion. Many in the SPD are inclined to go easy on Vladimir Putin, in contrast to the more hawkish Greens. There is likely to be a row over what to do about Nord Stream 2, the gas pipeline from Russia across the Baltic, which the Greens oppose and the SPD backs. Faultlines over how to punish Russia could end up casting a dark shadow over what should have been the new coalition’s honeymoon period.

5 — Investment versus debt

Scholz last month promised the “biggest industrial modernisation of Germany in more than 100 years”, and his coalition seems determined to invest billions in greening Germany’s economy and upgrading its infrastructure. But the FDP insisted it would also abide by the country’s strict fiscal rules — in particular its constitutional cap on new borrowing, the so-called debt brake. Squaring this circle could become one of the coalition’s biggest challenges. Its 177-page agreement offers hints of a solution: much investment will be carried out by KfW, a state development bank, Deutsche Bahn and a federal property agency that will be used to build new flats. There will also be one last borrowing binge next year while the debt brake — which was temporarily waived during the pandemic — is still suspended. But rows between the pro-investment Greens and the pro-fiscal rectitude FDP over spending priorities seem preprogrammed.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiP2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50L2EzMmIyZjBkLTUwODUtNDA4OC1iMTFkLTFkZWYyYjYxNTQxM9IBAA?oc=5

2021-12-08 05:01:00Z

1091307089

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar