Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has signed a deal to deepen defence co-operation with Ukraine in defiance of warnings from Moscow not to further arm Kyiv.

The Turkish leader struck a raft of deals on free trade and defence with Kyiv after three hours of talks with President Volodymyr Zelensky in the Ukrainian capital.

These include joint production in Ukraine of lethal drones, expanding a partnership that has seen Kyiv buy at least 20 unmanned aerial vehicles from Turkey — and deploy them against Russian-backed separatists.

Erdogan, who described Zelensky as a “dear friend”, restated his support for the “territorial integrity” of Ukraine and Crimea and his offer to act as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia. Turkey wanted to “ease tensions rather than fuel military escalation,” he said.

Describing their relationship as one of “real friends”, Zelensky thanked Erdogan for his mediation offer. “Today we have signed an agreement that will significantly expand the production of Baykar UAVs in Ukraine,” Zelensky said, adding: “These are new technologies, new jobs and strengthening Ukraine’s of defence capabilities.”

But Erdogan faces a tricky balancing act. The show of support by Turkey, a Nato member, for Ukraine belies a close but complex relationship with Russian president Vladimir Putin and significant Russian leverage over Turkey.

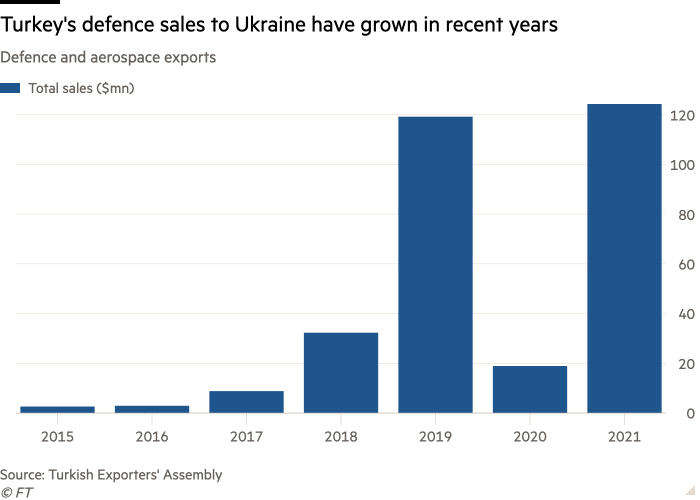

The Turkish president, for years accused by the west of turning towards Moscow and abandoning Nato, has not only repeatedly warned of the dangers of deeper Russian incursion into Ukraine but has also supplied the country with weapons including armed drones.

That support for Kyiv carries great risks for Turkey, analysts say, given its economic reliance on Russia and the risk that Putin could use gas, tourism, trade and the conflict in Syria as political weapons against Erdogan.

The Turkish president’s trip to Kyiv marked the 30th anniversary of bilateral relations and was long planned as part of a decade-long push to build economic, cultural and political ties.

The decision to go ahead with the trip despite the tense backdrop was viewed in Kyiv as highly symbolic. Turkey opposed Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, driven by a centuries’ long suspicion of Russian expansionism and concern for the Crimean Tatar minority.

But Erdogan’s relationship with Putin, however, has grown much closer in the years since then, spurred by his growing isolation from the west.

The Turkish president’s decision to buy a Russian S-400 air defence system in the aftermath of a 2016 coup attempt prompted claims that Turkey had abandoned Nato and led the US to expel Turkey from its F-35 fighter jet programme.

Despite warm personal ties between Erdogan and Putin, however, the two leaders have often found themselves competing rather than co-operating — especially in the realm of foreign policy. Turkish officials frequently point out that they have backed the opposite side to the Russians in conflicts in Syria, Libya and in the Caucasus.

“They are very proud of the fact that they are the ones confronting Russia on the ground [in these areas],” said a US official. “This is contradicted by the S-400 sale but it is also true.”

Moscow has been particularly irked by the growing defence co-operation between Turkey and Ukraine. Russian officials last October warned that Turkish drones could “destabilise” the frontline after Ukraine’s armed forces said a Turkish-made drone had destroyed an artillery unit belonging to Russian-backed separatists.

Even before Thursday’s deal, Ukraine had already acquired “around 20” TB2 drones, according to Vasyl Bodnar, the country’s ambassador to Ankara, with more expected to follow.

Kyiv has also placed an order for two Turkish warships, and Ukrainian defence firms are supplying engines for Turkish-made attack helicopters, cruise missiles and for a higher-spec Baykar drone.

Western nations have been buoyed by Ankara’s willingness to continue supplying weaponry. “Turkey’s materiel support to Ukraine has been substantial,” said the US official, adding that Washington would be happy if Ankara simply did “more of the same”.

Like Germany, however, Ankara is acutely aware of the pressure points that Putin could exploit if he felt that it had crossed a red line.

Turkey is heavily reliant on imported natural gas to fuel its power stations and heat its homes, and has already been suffering from shortages this year. Nearly half of Turkey’s gas supply came from Moscow in the first 11 months of 2021, according to data from the Istanbul-based energy consultancy IBS.

Putin has previously shown willingness to weaponise Russian tourists, who were Turkey’s top foreign visitors in 2019. He banned package holidays to the country in 2015 after the Turkish air force downed a Russian fighter jet near the border with Syria.

He also banned imports of Turkish tomatoes. Russia was the most important market for Turkish fruit and vegetable exports last year, generating a third of the sector’s $3bn in foreign revenues.

The potential economic disruption to Turkey is one of the reasons why Ankara is so eager to see tensions cool, said Burak Pehlivan, chair of the Turkish-Ukrainian Business Association. “Nobody in this geography will win from a conflict,” he said. “The most affected country after Ukraine and Russia would be Turkey.”

But the vulnerability that worries Turkey the most is Idlib, the last rebel-held province of Syria, where thousands of Turkish troops are policing an uneasy stalemate with the Russian-backed regime of Bashar al-Assad.

Erdogan is already under political pressure at home over the country’s 3.6mn Syrian refugees. Ankara believes that air strikes by Russian jets on civilian targets in the province earlier this month were a warning to Turkey — and to Europe — that Moscow could send millions more refugees its way.

Turkey’s weak spots mean that western officials are resigned to the fact that the country is unlikely to sign up to a new sanctions regime against Russia if an invasion does take place.

But the real challenge for Ankara, which polices the 1936 Montreux convention that governs access for warships to the Black Sea, would be what to do if Nato called upon Turkey to provide more military support.

“What happens if Nato wants to use Turkish military facilities to support maritime or air operations?” asked a defence official from another western country. “That would really put them in a really difficult position.”

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiP2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50L2UyYjdkZjQxLTZkYzYtNGVkNS04OGU1LWFiMDgxOTk2NzEzONIBAA?oc=5

2022-02-03 17:00:35Z

1249625977

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar